Note: I’m flexible about a lot that’s on this page. If you have a suggestion, please contact me.

On this page I go beyond the basic conventions that I believe everyone playing two over one game forcing should play (which I go over here) to create a strong card that will be fine for an intermediate or advancing player.

The card I discuss here is pretty full and no one should feel compelled to play everything on it. I suggest adding conventions only when you’re already comfortable with what you’ve been playing, and then only one or two things at a time. But eventually you’ll probably want to do most of the things shown here. And when you’re ready I’ve also written up an even more advanced card with lots of gadgets, but I suggest you not go there until you’re comfortable with everything on this page.

The conventions and treatments on this card are not necessarily what I consider best; in many cases what I suggest represents a practical compromise between technical perfection and memory strain, or sometimes just a concession to the practical reality that almost all of your potential partners play something a certain way.

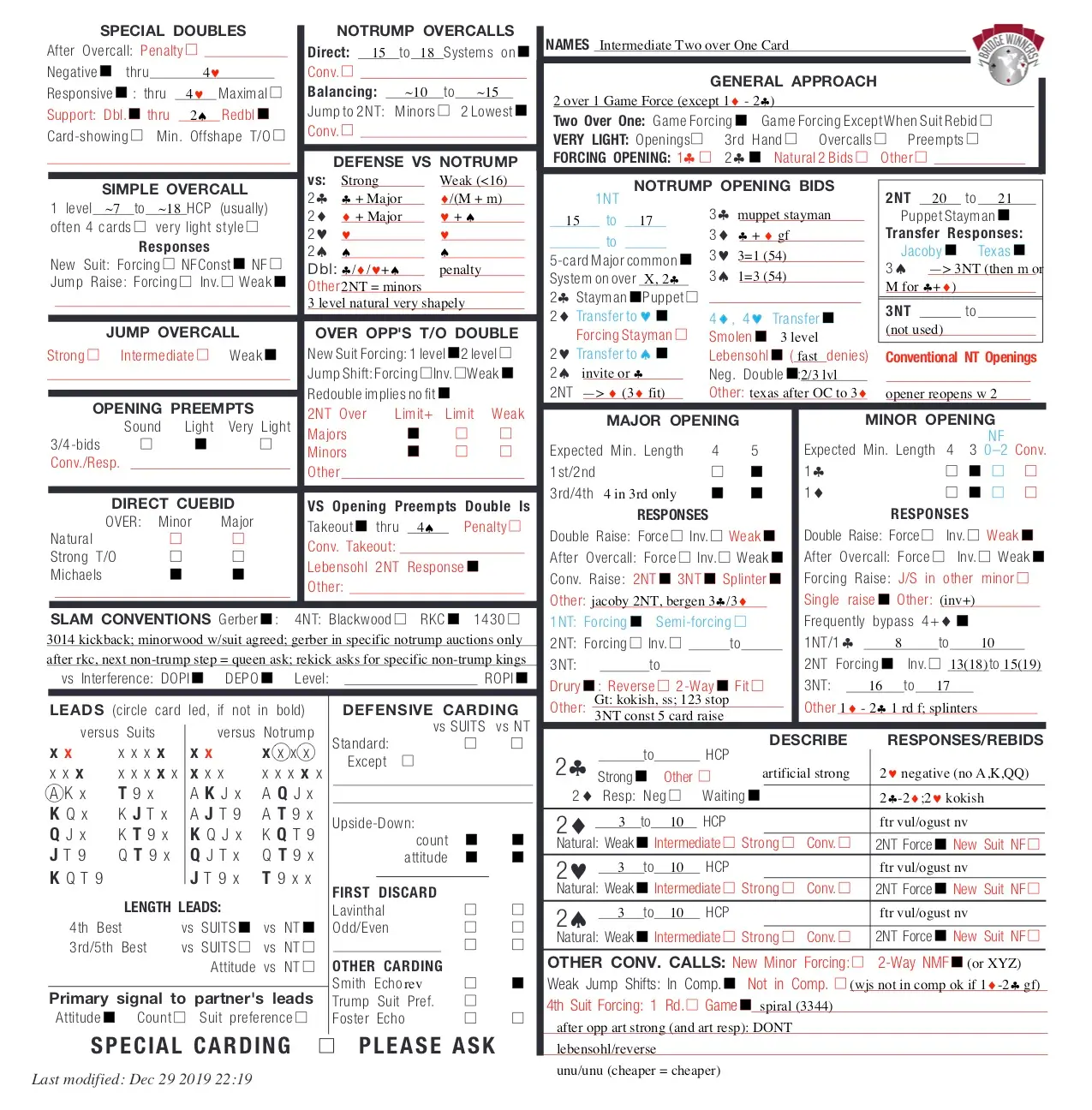

I start with an image of an ACBL convention card filled out with the conventions I’m recommending for an intermediate card (which I put together on the Bridge Winners forum1; you can view the card here). Below the card I explain most of what’s on it.

NAMES

Write your name, and your partner’s, on this line; it’s nice to have your ACBL numbers here too for filling out entry forms and so forth.

GENERAL APPROACH

2 over 1 Game Force (except 1♦ – 2♣). It’s fine to have every two over one create a game force but I do think it’s slightly better to make an exception for the specific sequence 1♦ – 2♣, which can be invitational or better. This isn’t very important so if you don’t like having exceptions, straight two over one is fine.

NOTRUMP OPENING BIDS

I add a fair amount to the beginners’ card in this section.

1NT Range: 15 to 17. Weak notrump players can use pretty much the same stuff after notrump openings —I do even when I’m playing 1NT as weak as 10-13 — but the effects of the notrump range ripple through the rest of the card so even though I prefer playing a weak notrump I don’t discuss that here.

5-card Major Common. You should be opening every 5-3-3-22 hand in your notrump range 1NT even when you have a five card major. When your suit is hearts the statistics are clear that opening 1NT is better; with a spade suit it’s too close to call and in my opinion it’s best to treat the two suits the same.

Systems on after: double and 2♣. In the past I’ve said double and artificial 2♣ here, but the distinction isn’t important, as you’ll see when we get to doubles: If systems are on after 2♣ then double is stayman, while if systems are off after a natural 2♣ then double would be takeout, which works almost the same. This is simpler to remember so I’m going with it.

After interference higher than two clubs, systems are off: Suit bids at the two level are natural and nonforcing, and starting at 2NT we use lebensohl. If the interference is at the three level you have some guesswork to do but suit bids at the three level are natural and nonforcing. The exception to systems being off is texas transfers, which are still on as long as they’re jumps.

2♦ Transfer to ♥ and 2♥ Transfer to â™ . I’ll mention here: Responder’s new suit rebid after a jacoby transfer is natural and forcing (but not necessarily all the way to game). Note that under the new alert procedure you announce “hearts” or “spades”.

2â™ : Range ask or clubs. Opener treats 2â™ as a balanced invitation, rebidding 2NT to decline it (with a minimum) or 3♣ to accept. If responder has a balanced invite she3 will pass 2NT and correct 3♣ to 3NT; if she was transferring to clubs she’ll bid 3♣ herself, pass if opener bids 3♣, or bid another suit at the three level to show a game forcing hand with clubs. Treatment of the new suit bid varies but when playing a strong notrump it’s normal to have any new suit ostensibly show shortness in the bid suit; it may be a choice-of-games bid, or later turn out to be an advance control bid as part of a slam try in the minor. It’s also reasonable to play that 3♥ and 3â™ each show four cards in that suit (playing this way this is how you handle game forcing hands with a four card major and a longer minor; do this if you want stayman-then-bid-a-minor to be nonforcing), meaning 3♦ is sort of a generic “what do you think about our fit” kind of bid. I play the latter way only when using a weak notrump, but either way is fine.

2NT (response to 1NT): Transfer to diamonds. Opener bids diamonds with a fit, clubs otherwise, which allows responder to use this with the rare weak minor two suiter (weak enough that you’re confident 1NT won’t make) with which she can try passing the 3♣ bid. Note that transfers to minors are now announced (say “diamonds”); the fact that it’s still shown in red is an anachronism, which will be corrected when the ACBL’s new convention card is released later this year.

3♣: Modified puppet stayman. Though it’s fine to play a 3♣ bid as regular puppet stayman, this modification is a little bit better. In this version, opener rebids 3♦ with any hand having no five card major regardless whether he has a four card major. (When using regular puppet, opener distinguishes immediately between hands that have one or both four card majors and hands than don’t.) Responder can then use smolen to try to find a four-four fit in her major; this approach limits information leakage as we never reveal whether opener has four cards in any major responder doesn’t care about. The disadvantage is that responder can’t use it if she has two four card majors; regular (two-level) stayman needs to be used for that instead. (This disadvantage is the reason the modification doesn’t work after a 2NT opening.)

If you don’t like this modification play regular puppet stayman instead; the advantage of modified puppet is small.

3♦: 5/5 minors, game forcing. We don’t play minor suit stayman but this captures a lot of the hands that would use it. (With 5-4 in the minors we will usually use our 3♥ and 3â™ bids; we do lose the 4-4 minor suit slam hands but those are very rare.) Opener shows that he likes clubs by bidding 3♥, and diamonds with 3â™ ; 3NT denies a good hand for a contract in either minor.

3♥: 3=1-(5-4), game forcing. Responder shows a singleton heart, three spades, and 5-4 either way in the minors. Usually she’s angling for 3NT or 4 of the major (possibly on a 4-3 fit when the other major is unstopped), but sometimes these auctions end in a minor suit at the game or slam level. Followups are natural.

3♠: 1=3-(5-4), game forcing. As with 3♥ but with the major suit lengths reversed.

Side note on other response schemes, which you can feel free to ignore:

You’ll see many sets of responses to a 1NT opening out there. Most have their advantages and are at least reasonable to play, but I’ve put a lot of thought into the choices I’ve suggested on this page. Here are some thoughts about some other conventional responses you might be considering playing:

2â™ transfer to either clubs or diamonds (usually in conjunction with 2NT natural and invitational): 2â™ is first treated as transfer to clubs, with responder next correcting to 3♦ if she wants to play that contract. This one’s common among gold-rush level players, much less so among more experienced players. I think the main lure is the natural, invitational use of 2NT, which makes newer players comfortable, but there’s significant cost: Unless you have fairly sophisticated followups (and just about nobody who plays this treatment does) there’s no good way to distinguish between a slam try in clubs and one in diamonds. You could play that a subsequent 3♥ bid shows a strong club hand, 3â™ shows strong with diamonds, or even some more complicated relays, but this gives up lots of definition for a minuscule gain. In practice most people using this methods are doing so only to get out in three of a minor, which isn’t something you want to do very often after a strong notrump opening. I suggest that if you’re going to the trouble of playing transfers to minors you should use a method that optimizes slam sequences, which are much more important.

2â™ minor suit stayman (promising at least 4-4 in the minors; responder has either a very weak minor two suiter or a game forcing strength with no interest in the major suits. (Some versions don’t include the weak hands). This convention is fairly useful when it comes up, and I think it’s close whether to play four suit transfers, as I recommend, or a minor-suit-stayman based system. Be sure you discuss followups with your partner, as there’s no universally agreed upon method.

3♣ 5-5 minors weak and 3♦ 5-5 minors game forcing. Usually in conjunction with 2â™ transfer to either minor and 2NT, which I discuss (and criticize) above. This method is OK (though the systems it usually goes with aren’t). Having a way to show a strong minor two suiter is good and I do use 3♦ this way; I suggest handing weak 5-5s differently because I want to use 3♣ for modified puppet stayman but this is fine too (though it rarely comes up).

3♦ 5-5 majors (with strength variable; I’ve seen it played as both intermediate and game forcing). I suppose doing this with intermediate-strength hands is fine when it comes up (because as transferring to spades and then bidding 3♥ is forcing, so there’s no great way to invite with this shape), but that’s a very narrow target that takes away a very useful bid, so I don’t recommend it. On the other hand, if you are still uncomfortable with the idea of looking for minor-suit slams then I guess you might as well do something like this. the real solution to the 5-5 invitational hand is to play second-round transfers, which I discuss on my advanced conventions page.

3♥ 5-5 majors invitational and 3â™ 5-5 majors game forcing: As I explain above, having a bid for the 5-5 invitational hand is nice, and using 3♥ for it is probably better than using 3♦ (because 3♦ leaves more room so is more profitably used for minor-suit-oriented hands). On the other hand, the 5-5 game forcing hand is easy to describe without this treatment so I don’t like taking away an otherwise-useful bid for it.

3â™ transfer to 3NT (with various followups). This can be useful but requires a ton of discussion to make it work. I do like doing this after a 2NT opening but there it’s necessary because you otherwise lack the room to handle minor-suit-oriented hands adequately.

3NT transfer to 4♣ (with various followups). Theoretically a good thing when played in conjunction with 3â™ transferring to 3NT, but let me be clear: You should not play this. Why not, if it’s theoretically good? Because you will forget. Or your partner will. And the damage when that happens is huge. Like it or not, 1NT – 3NT sounds so normal, natural, and passable that all but full-time players need to play it that way.

It’s not shown on this part of the card but responder’s jump to 4♣ is gerber. Play regular, vanilla gerber (4♦ shows zero, 4♥ one, and so forth), not some keycard-y variant thereof. And please recall that if responder next bids 4NT, after getting a response to gerber, that’s to play.

4♦, 4♥ Transfer. Note that a jacoby transfer followed by 4NT is a natural choice of strains (notrump or the major) slam try; after a texas transfer, the major is set as trump and keycard (whatever kind you play) is on. And a jacoby transfer followed by a raise to game in the major is a slam try, usually balanced; an unbalanced major suit slam try would use a jacoby transfer followed by a splinter bid.

Smolen at the 3 level. After a 2♦ answer to a 2♣ stayman bid, 3 of either major (a jump bid) by responder shows game forcing strength and five cards in the other major (and therefore four in the major bid, else why use stayman…). This is how we handle 5-4 major suit hands with game forcing strength. With 6-4 (either way) in the majors, either suppress the four card suit entirely (i.e., transfer instead of using stayman) or use stayman, then a delayed texas transfer (a jump to the four level) to the six card suit if you don’t find a 4-4 fit.

Lebensohl (fast denies). I won’t go into details here as there’s a lot to it, but you should play lebensohl (or the transfer variant thereof). I prefer the fast denies version primarily because it’s far more common than the alternative so it’s probably what your potential partners already do, but fast shows is perfectly fine too. Ron Anderson’s book on lebensohl is a pretty good treatment of all things lebensohl. Note that whether you play lebensohl has nothing to do with what meaning you attach to doubles (see next).

Negative Double at the 2 and 3 level. I’d prefer these were called takeout doubles as they are typically takeout of a single suit (the one bid by the opponents), but no matter what you call them these are good to play — somewhat better than penalty doubles and loads better than stolen bid doubles (which are atrocious). Basically, responder’s double of any natural suit bid (i.e., it shows the suit bid, either alone or plus a second suit, whether known or unknown) at the two or three level is takeout, showing shortness in the suit doubled and sufficient values to compete. Opener can leave the double in with length in the opponents’ suit, so responder shouldn’t double with a very weak hand; many players require invitational values but I consider that too limiting, just be sure to have the balance of power.

Playing takeout/negative doubles, what if responder wants to penalize? She passes, and opener is required to reopen with a double any time he has shortness (a doubleton) in the suit bid. (If he has three in the suit you may be out of luck because he’ll pass the deal out — when the good guys’ trumps are 3-3 you may not be able to double the opponents even when they’re going down, and when they’re 4-3 and somehow stop there anyway you’ll soon be racking up undoubled overtricks. But 3-3 is a fairly narrow target and playing penalty doubles doesn’t solve the problem either; holding more trumps than that very rarely happens in the modern game.

It is common to play takeout/negative doubles at the three level only and something else (usually penalty or stolen bid, sometimes “cards”) at the two level. This approach is an improvement over not playing takeout doubles at all but it doesn’t go far enough because responder can’t handle her hands that want to compete, don’t have a suit of their own, and can’t force to game.

Side note about stolen bid doubles: They stink. The reason is that if you’re playing stolen bid doubles you miss both many of your 4-4 major suit fits and almost all of your opportunities to penalize the opponents; the first of those problems is moderately serious and the second is a huge problem against opponents who overcall aggressively.

To see why, consider for example what options you have as responder after partner’s 1NT opening is overcalled with a 2♦ bid that actually shows diamonds (if the opponents are bidding naturally, or for example if they play DONT wherein it shows diamonds and a major). If you have a five card heart suit you can double to transfer to it, and 2♥ transfers to spades, so the major suit one-suiters hands are handled. And the minor suit hands can run through lebensohl. But what if you have a four card major you’re interested in playing in? You’re out of luck unless you have game forcing strength (which would allow you to cuebid as a stayman substitute, either immediately or after a lebensohl 2NT if you play that), but often you will want merely to compete, not drive to game. Playing stolen bid doubles it is impossible to get to a 2♥ or 2â™ contract unless responder has five of the major. And what if you want to penalize a overzealous opponent – say you have four diamonds and a scattered seven count? You can’t — double isn’t penalty and if you pass and so does LHO, partner won’t reopen with double unless you have made the agreement that he has to.

And what about if you agree to reopen with double? Some of the above problems can be solved if partner always reopens with shortness in the opponent’s suit, but that helps only when responder wanted to penalize or when she can scramble to a playable fit; it’s useless when responder is the one with shortness but no suit of her own and opener with length. To handle those responding hands you need to play takeout doubles; now whichever member of the partnership has shortness in the opponent’s suit doubles, and partner leaves it in when that looks right and bids on otherwise. The bad guys can escape undoubled when our trumps are divided 3-3, but few methods handle that problem well. (Only a “cards” double will get ’em when we have the balance of power and three trumps apiece, and that method suffers on all other holdings.)

2NT: 20-21 (but good 19s aren’t uncommon).

Jacoby and Texas transfers.

Puppet Stayman. Even if you play 3♣ modified puppet after 1NT, play regular puppet here (because the modified version doesn’t work when responder has both majors). Note that it’s not alerted when it’s not a jump, but opener’s rebids are.

3â™ puppet to 3NT, followed by minor suits. With one minor and game forcing strength (and usually with slam inspirations as we’re automatically higher than 3NT), rebid the suit at the four level after opener’s forced 3NT. With a two suiter rebid 4♥ or 4â™ , showing a singleton or void in the suit bid and length (usually 5-5) in both minors.

Not used, but acceptable: Gambling 3NT, a 3NT opening showing a solid seven card suit (usually a minor) and nothing else. I don’t particularly like this because it wrongsides the notrump (opener has no tenaces to protect and nothing to hide, while partner may have holdings that benefit from being led up to), but I can live with it if partner insists on it. If you’re not playing gambling notrump and you pick up a solid eight card or minor, please don’t open it above the level of 3NT, because the latter will often be the best contract; open 1 of the minor instead.

MAJOR OPENING

Expected Minimum Length: 5, but 4 by a third seat opener. 4 card major openings (by minimum hands only) in third seat are effective and you should employ them; you’ll usually want to have a reasonably strong suit because partner will raise you with three and will often lead the suit if your LHO declares.

I don’t open four card majors in 4th seat but some good players do.

Double Raise: Weak. Promises four card support. When not vulnerable, can be very weak, but beware flat hands. Alerted. Works only when playing something else, e.g., bergen raises, for invitational raises. I’m sort of on the fence about what’s better, bergen raises plus weak jump raises, or the more standard invitational raises; today I prefer bergen but tomorrow I might feel differently, and if you have a strong preference either way I say go with it. These days many strong players have switched to playing the jump raise as mixed, hiving up the ability to jump with a weak hand unless you’re willing to commit to the four level; I’m not sure how I feel about this treatment.

After Overcall: Weak. Regardless how you play your double raises in uncontested auctions, nearly everyone plays them weak in competition and you should too. Not alerted.

Conventional Raise: 2NT and Splinter. 2NT is the jacoby 2NT convention, an artificial bid showing four or more card support for opener’s major and game forcing strength; responses to it are conventional (and alerted). Splinter bids are double jumps (i.e., to 3â™ or the 4 level) into new suits promising game forcing strength, four card support for partner’s suit, and a singleton or void in the suit bid.

You may hear some players say that hands with slam aspirations shouldn’t splinter bid, because they won’t know what to do if partner signs off in game. That approach is understandable but not we can do better: When you have the shape for it and sufficient strength to force to game, make a splinter bid with either a seven loser hand (which will respect opener’s signoff) or with five loser or better (which is enough playing strength that you can make another slam try even opposite a minimum). It’s the six loser hands that are the problem; with those try something else, either a jacoby 2NT or a two over one response.

If you find the reference to some-number-of-loser hands confusing, check out the presentations I have given on the losing trick count (part one and part two).

There’s no convenient place for it on the card but in general, other unnecessary jumps into new suits are also splinter bids, usually in support of the last-bid suit. For example, If the auction proceeds 1♦ – 1â™ ; 4♣, the 4♣ bid is a splinter bid with spade support (4 or more spades, and enough strength to bid game opposite what responder has promised, which isn’t much). We say it’s an unnecessary jump because with a real club suit opener could force with 3♣; the extra level distinguishes the bid as a splinter.

Major suit stuff that may not all fit in this part of the card:

Bergen 3♣ and 3♦ raises. There’s more to the bergen raise system but this is all you need. I play that 3♣ is the weaker of the two bergen raises (“regular bergen”) but some players reverse these two responses; it barely matters one way or the other. Bergen raises are on after a double (unless you play something else, which I do on my advanced card) but not after an overcall.

Bergen raises are optional; I’m sort of on the fence about them. If you don’t play them then your jump raises should show four cards and game-invitational values; jump shifts to 3♣ and 3♦ can be natural and weak, fit jumps, or something else.

Kokish game tries. After 1♥ – 2♥ and 1♠– 2â™ , the next bid up (2â™ or 2NT) asks responder to show what suit(s) she would accept a help suit game try in (meaning, in part, which suits responder has values in; without extra trump length, shortness should usually not be considered “help”); with more than one such suit responder bids the cheapest. Note that after 1♥ – 2♥; 2â™ , a 2NT rebid shows that responder would accept a game try in spades (the cheapest suit-showing bid). Responder returns to 3 of the trump suit with no side suit values to show. If opener needs to know about a suit responder hasn’t answered about yet (because she showed acceptance of a lower suit), he next bids the suit he cares about.

Note that opener can make a kokish “game try” even with a slam-invitational hand; if he bids on after a signoff this confirms slam aspirations.

Short suit game tries. If playing kokish game tries you don’t need new suit bids to show length or values, so instead we use them to show shortness (singleton or void); responder evaluates her hand for game knowing of the shortness. (Often this is actually a slam try so responder should usually not jump to game with a good hand and a good fit; instead, control bid in case opener is slamming.)

1-2-3 stop. In the auctions 1♥ – 2♥; 3♥ and 1♠– 2â™ ; 3â™ , opener’s rebid shows a desire to shut the opponents out, not interest in game. This works only if you have artificial game tries available, in our case kokish and short suit tries. Not very important as the opponents haven’t bid yet so they often won’t, but no other use is terribly useful either. With one partner I play this as a “power try”, asking responder to bid game with lots of high card points, but that hand can usually be handled via a kokish try; with another I play it as a “trump try”, asking partner to bid game with good trumps (king-queen or better, let’s say), which is nice when it comes up but that’s rare. Whatever you do here, it’s not likely to come up a lot.

1NT Forcing. Note that it’s not forcing by a passed hand; a third- or fourth seat opener will pass a 1NT rebid with a balanced minimum.

Reverse 2-Way Drury. 2-way drury, wherein 2♣ shows a three card raise and 2♦ promises 4, is nice but not necessary; one way is almost as good. I generally play that drury applies after RHO’s double, but not after an overcall; opinions differ on this one so check with your partner. “Reverse” means opener returns to the trump suit with no interest in game.

A few players reverse the meanings of these two bids, using 2♣ for a four card raise and 2♦ to show three, but I believe that’s not a good idea, because having extra room above the three-card raise is a little more valuable. It’s close, though.

If playing 1-way drury I don’t require limit raise values, but rather something like 8 or more (meaning a simple raise can be very weak); opener should often make a counter-try with 2♦ rather than jumping to game. Playing 2-way drury this works only with the 3-card raises.

Whether a 2♣ drury raise shows exactly three, or three or more, when spades is the trump suit a 2♥ rebid by opener is natural, showing a four card heart suit, and is a one round force. This lets us capture some of our 4-4 fits, which often play better than the 5-3s. An alternative method is to play that a 2♥ bid is natural (showing four hearts) but not forcing, just looking for a better contract; with a game force and four hearts, opener rebids 3♥. This second method is probably better but differs from how drury is usually played, so discuss it with partner before springing it on her.

MINOR OPENING

Expected Minimum Length: 3 (for each minor). With 4=4=3=2 I open 1♦, but if you open 1♣ with that shape, meaning your 1♦ opening always shows four cards in the suit, that’s fine too. (You’ll need to announce “could be short”.)

Double Raise: Weak. Part of inverted minors. Alertable even though it’s the most common treatment.

After Overcall: Weak. Not alertable.

Forcing Raise: Single Raise. Part of inverted minors. Alertable. I prefer to play that after this start the auction can stop in 2NT or three of the agreed minor, but many people play that it’s game forcing, period, and that’s OK too. See the discussion below (at “2NT Forcing”).

Frequently bypass 4+ ♦. A standard part of “walsh” style 2/1: bid a four card major if you have one, even with longer diamonds, unless you have game forcing strength.

1NT/1♣: 8-10. Many people play that a one notrump response to a 1♣ opening shows anywhere from 6 to 10 high card points (and denies a four card major, which responder would bid instead of notrump), but I prefer to bid 1♦ instead with a minimum (5-7) hand even when it doesn’t have a long diamond suit, reserving an immediate 1NT for stronger (8-10) hands; this approach means notrump is rightsided more often (when opener has 11-14 and responder 5-7). This isn’t very important so if your partner doesn’t like it that’s fine, use 6-10.

2NT Forcing (13-15 or 18-19): Most players these days play a 2NT response to a one of a minor opening as invitational (11-12) but I prefer that it be game forcing; invitational-strength balanced hands that don’t have a four card major start with a single (forcing) raise of opener’s minor, planning to rebid 2NT. This is the main reason I prefer to play inverted minor raises as forcing but not necessarily all the way to game; with a balanced 11-12 responder makes an inverted raise and then rebids 2NT, which is nonforcing. If your favorite partner isn’t comfortable with this that’s OK, you can play it the 2NT response as invitational, but I do think the approach I suggest here is better.

3NT: 16-17. If you play 1m – 2NT invitational then you’ll probably want to write 13-15 here; I don’t love this sequence when responder has a minimum game force because it takes away lots of room so you can’t check on stoppers (I don’t like watching the bad guys take the first five tricks against my 3NT contract when we could have bid and made five of a minor instead). Your choice. Note that balanced responding hands with 18 or more points and no suit to bid need to do something else — some forcing bid — no matter which way you play, lest you miss 6NT with, say, 18 opposite 14: 2NT if you play that as forcing as I suggest, an inverted minor suit raise if 2NT isn’t forcing. In each case you’re planning on inviting slam with a 4NT rebid at your next call.

TWO LEVEL OPENINGS

2♣: A 2♣ opening is artificial and strong (generally at least 22 HCP or nine very likely tricks, but you don’t have to define this carefully). A 2♦ response is waiting, meaning it doesn’t say much except that responder has at least something — an ace, a king, or a couple of queens will do. A 2♥ response is artificial and negative (and is alerted; a 2♦ response is not alerted regardless what it means), saying responder has basically nothing; if responder bids anything other than 2♥ then the partnership is forced to at least the game level. Other responses in suits show at least five cards and a good suit (at least two of the top three honors); responder should never bid notrump at her first call.

It’s perfectly fine to play something else here instead: I don’t love the 2♥ negative approach, I just dislike it less than I dislike other methods. Methods I have recently seen in use:

- 2♦ is an artificial waiting bid, including almost all hands; responder bids the cheapest available minor suit at her next call as an artificial negative while all other rebids are natural and establish a game force. This is fine when it works out but the auction gets awkward when opener’s next bid is 3♣ or, worse, 3♦, and responder hasn’t yet shown a bust. Opener should keep this problem in mind when deciding whether a minor-suit-oriented hand is strong enough for a 2♣ opening.

- 2♦ waiting and nearly automatic, and no way to distinguish between terrible and all other responding hands other than passing below game. I don’t think this is very good but I know good players who like it.

- 2♦ waiting and positive (as in the method I recommend); bad hands bid their longest (five card or more) suit immediately, or notrump with no five card suit. I played this a few times with a partner who loved it and I can confidently report that it is terrible; do not play this way. A variation I came up with would be for 2♦ still to be waiting and game forcing and to have all bad hands transfer to their suit (or transfer to 2NT, using a 2â™ bid, with no suit worth showing); doing things this way would be better except when responder has a bad hand with hearts and you’re at the three level already with no known fit. I suspect this modification would be better than the original and it may even work OK (I don’t know for sure as I’ve never played it) but I still don’t recommend it.

- Control-showing responses. Counting an ace as two “controls” and a king as one, responses are in steps as follows: 2♦ shows 0 or 1 control, 2♥ two controls, 2â™ three controls, and so on. A reasonable variation is to have 2â™ show three controls comprising an ace and a king, while 2NT show three controls that happen all to be kings (which might be worth protecting from the opening lead, which you just did a lot of the time by having responder bid notrump first). This method is reasonable. Another variation changes the scale a bit, with 2♦ showing zero controls, 2♥ one, and so on; again, reasonable. Controls matter a lot opposite 2♣ openers so this method helps the partnership get to the right level, but it can make finding the correct strain more difficult.

- Point count responses. A 2♦ response shows 0-3 HCP, 2♥ 4-6, 2â™ 7-9, and so on. Or the ranges can be a little different. This method is substantially worse than the control-showing version because mere high card points can mean nothing opposite a shapely 2♣ opening hand while control cards are usually good to know about, so I don’t recommend anyone play this way.

- Another twist: some people who play 2♥ as an artificial negative, as I recommend, use a 2NT response to show a positive response with biddable (KQxxx or better) hearts. I don’t recommend this — if you have a game forcing hand with hearts, either bid 2♦ waiting or, if your hand is pretty one dimensional, respond 3♥ — but it’s not terrible and I play it if my partner wants to.

2♦, 2♥, 2â™ : Natural and weak; usually a six card suit. You can write down 3-10 HCP but this varies by vulnerability and position (second seat openers shouldn’t use weak twos as much, third seat should do so very frequently, and fourth seat never should). New suits by responder are forcing; 2NT asks about opener’s hand. It’s up to you whether the answer should show a high-card feature in a side suit, or ogust responses (3♣ bad suit and weak hand, 3♦ good suit and weak hand, 3♥ bad suit but strong [in context] of the opening preempt hand, and 3â™ a good suit and a good hand; each of these rebids is alertable), as the two are about equally useful. If you’re up to it play feature responses when vulnerable and ogust when non-vulnerable; the idea is that you’re vulnerable weak twos are a lot more likely to include some side suit strength while your nonvulnerable openings can be so weak that that it’s important for responder to have a way to tell. But if the complexity of playing different methods according to vulnerability bothers you, no big deal, just pick one and play it always.

By the way, I said above that 4th seat should never bid a weak two, so what should a fourth seat opening of 2 diamonds, hearts, or spades show? I suggest this show a minimum full opener (with less you could pass the deal out), say in the 13 to 16 high card point range, with a good 6 card suit; responder should be able to estimate the game prospects pretty well after such a specific description.

And while we’re at it, a fourth seat three level opening is similar to the above (13 to 16 points with a good suit), but with one more trump (i.e., a seven card suit).

OTHER CONVENTIONAL CALLS

2-Way NMF (New Minor Forcing). A misnomer, this is more properly called 2-way checkback because often the minor isn’t “new”. Most 2/1 players play regular new minor forcing (not 2-way), but I prefer 2-way checkback because it’s far easier to learn and use and it gives up almost nothing. But if you don’t know it yet, using regular NMF here is fine. Each version is alerted.

I won’t go into all the details but in 2-way checkback, a 2♣ bid by responder, after the auction has gone one of a suit – one of a suit; one notrump, is an artificial puppet to to 2♦; after opener makes the (forced) 2♦ bid, responder either passes (to get out in 2♦) or bids naturally to show some invitational-strength hand. With game forcing strength responder’s second call is an artificial 2♦ bid, after which bidding is natural. a 2♥ or 2â™ rebid by responder is natural and shows less than invitational strength. 2NT is a puppet to 3♣ (not a natural bid), and three-level suit bids are natural and forcing, showing strong suits and game forcing strength.

If this looks a lot like XYZ (if you know that), that’s because it is: XYZ sequences are exactly the same, they just apply more broadly.

Weak Jump Shifts in Competition. When the opponents double or overcall, it’s common to want to preempt them and rare that we need to have a delicate slam-going auction, so weak jump shifts work well here. Against silent opponents I mildly prefer responder’s jump shift (i.e., a jump bid into a new suit) to be game forcing. Not alerted.

Other uses are fine too, if you know them.

4th Suit Forcing to Game. A normal part of 2/1. Some play that’s it’s only a one round force, but this way is simpler and arguably better. Note that a passed hand cannot create a game force, so a fourth suit bid by a passed hand is natural. Alerted.

Other side of the card…

SPECIAL DOUBLES

Negative Double through 4♥. This applies when our side opens with one of a suit and LHO overcalls; the level referred to is opponent’s overcall. If LHO overcalls 4â™ or higher, double is penalty. Negative doubles show the unbid suits, more or less, with at least some emphasis on any unbid major.

Note that negative doubles apply only when we opened at the one level; if opener preempted then his hand is presumed to be known, and responder’s double is for penalties.

Responsive Double through 4♥. Similar, but this time it’s for when our side has made an overcall or a takeout double; the level referred to is that of the bid right after our overcall or double. A responsive double by advancer (partner of the doubler or overcaller) shows either both majors (if neither has been bid) or both minors (if neither has been bid) and asks partner to choose.

Support Double through 2♥. Support doubles are optional and I might have left them off the basic card, but I do think they’re a good idea. They apply to auctions in which we open with one of any suit, responder bids one of a major suit (whether second hand has passed or doubled), and third hand overcalls; opener’s double shows exactly three-card support for responder’s major and therefore an immediate raise shows four. The level referred to is the level of the bid that we are doubling to show support. For example, after 1♣ (pass or double) – 1â™ (2♥), double by opener would be a support double.

It’s possible to play support doubles after responder bids 1♦ (with the double showing three card diamond support), but it’s fairly rare and I don’t recommend it. Note that the robots on BBO do it, for whatever that’s worth.

Even if you play support doubles and the situation for making one arises, you don’t have to use it; if opener judges that there’s a better action (including passing) he can elect that instead.

Support Redouble: Applies in auctions in which a support double would have had fourth hand overcalled, but this time fourth hand doubles (usually for takeout but it doesn’t matter unless it’s agreed to be penalty, which would be unusual); redouble shows a three-card raise of responder’s major. If fourth hand’s double is penalty (which I guess is conceivable after the auction begins 1 of a suit (X) – 1M, and wouldn’t be alerted — essentially no doubles are — so you’d need to ask) then redouble says it’s our hand (meaning we plan either on doubling the opponents or outbidding them; they can’t play undoubled); interestingly, when opener has non-minimum values and exactly three card support this will still often be the right call, even though it no longer explicitly shows support.

SIMPLE OVERCALL

Strength: ~7 to ~17 points (but it’s not really about high card points). This is a very wide range but in practice it works fine; methods that require intervenor (the player who either overcalls or doubles) to double with any 16 point or stronger hand get very tricky to use well in competition. You should include something for shape here, so 17 high card points in a very distributional hand is too strong. Note that the range I list here is very slightly lower (no 18 point hands) than on the basic card; as you get more experienced you’ll get a little more comfortable with double-then-bid with your strong hands. But it’s never completely safe to make a takeout double without support for a suit partner might bury you in, so we still keep our overcalls potentially heavy.

New Suit Non-Forcing Constructive: A compromise between two imperfect extremes; a new suit (not a raise or a cuebid of opponents’ suit) by advancer (the partner of the overcaller or doubler) shows some values (“constructive” — think something like 7 or more, or a bit less with a good suit) but is not forcing (so advancer has to do something else with a good fit or a game force). This isn’t a great method but those that are clearly better are also pretty complicated, and this is how a majority of your potential partners probably play.

Jump Raise Weak: As in most other competitive auctions, jump raises are weak, in part because shutting out the opponents is good and in part because strong raises can use a cuebid.

OPENING PREEMPTS

3/4 level openings light: This is pretty normal and notice it’s not well defined. When you’re not vulnerable, almost any hand with a seven card suit will do for a three level opening in first or third seat, if it’s too weak to open at the one level. (It’s better to have no honors at all than a few in side suits and none in the long suit.) Some players “downgrade” seven card suits to weak two openings if the suit quality is bad, but I recommend against that practice because it makes life hard for partner.

DIRECT CUEBID

Michaels (over minors and majors). Shows at least five cards in each of two suits: both majors, if the opening was in a minor; the unbid major and one of the minors, if the opening was in a major suit. Please don’t do it with only 5-4 (usually with five cards in the lower suit; with five of the higher suit and four of the lower it’s clearly better simply to overcall in the five card suit) unless you have an agreement with partner to do so (lest he choose poorly on the assumption you have more shape than you’re promising); I don’t like that agreement but I guess it’s OK if your hand is fairly “pure”, i.e., no minor honors in the short suits.

The way I play, a michaels bid can show just about any strength, but some play that it’s either pretty weak or quite strong (strong enough safely to bid a second time), not in between, and that’s OK too.

If you do play it wide ranging, here’s a nice adjunct I recommend if you can remember it: Most players play that after a michaels bid over a major opening, i.e., one showing the other major and an unknown minor, 2NT asks intervenor to bid her minor. A better method is to play that 3♣ by advancer is pass or correct (to diamonds), while 2NT is a strength ask: intervenor bids her minor (3♣ or 3♦) with a minimum-value michaels hand, 3♥ or 3â™ with a maximum (with 3♥ showing a club suit and 3â™ showing diamonds). All this method gives up is a natural, forcing 3♣ bid, which isn’t very useful.

After a michaels overcall of a minor suit (i.e., one that shows both majors) you can use a cuebid by advancer (i.e., 3♣ or 3♦) to ask for partner’s better major, which is particularly useful if intervenor will use michaels when 4=5 in the majors. 2NT can be either natural and invitational, or a strength ask; I’m not sure which I prefer but be sure not to try it unless you’ve agreed on one or the other.

I mildly prefer other methods but michaels is fine and very common.

NOTRUMP OVERCALLS

Direct: 15 to 18 HCP, Systems on. Note that this is slightly stronger than our opening notrump range. A stopper in opponent’s suit is nice to have but not strictly required, but do have a balanced hand. (If you have no stopper you’ll probably find another call; with no stopper, no suit to bid, the wrong shape for a takeout double, and a minimum for this bid (15 HCP or so), you’re probably better off passing if the opponent’s suit is a major). “Systems on” means advancer (partner of the overcaller) bids exactly the same as he would if responding to an opening 1NT bid (except for allowing for the tiny strength difference), as if the other side hadn’t opened at all.

It’s not shown on the card but a 2NT overcall of an opponent’s weak two opening is pretty similar, showing a good 15 to 18 or 19 high card points, a balanced hand, and this time definitely a stopper or two in opponent’s suit. Advancer uses the same system he would when responding to a 2NT opening (in other words, if you use puppet stayman then it applies here too, and so do jacoby and texas transfers).

Balancing: ~10 to ~15 HCP. This applies to auctions that begin with one of a suit by the bad guys followed by two passes. It’s possible to play the range a little narrower, and when vulnerable I wouldn’t bid it with a ten count. You’ll usually have a balanced hand (or you’d be overcalling instead), but this time a stopper in opponent’s suit is not required. It’s common to play the same systems by advancer of a balancing notrump as you play by responder to a 1NT opening (i.e., “systems on”), although the issues are a little different and it’s also reasonable to play everything natural (i.e., “systems off”). I prefer systems off.

Jump to 2NT: 2 Lowest. The “unusual notrump” shows the two lowest suits that the opponents haven’t bid. Note that not all 2NT bids are unusual; it has to be an overcall (i.e., the opponents opened the bidding), it has to be a jump bid [there are some rare exceptions that you can ignore for now] and it applies only if partner hasn’t done anything but pass. In most circumstances you really should have five or more cards in each suit, but the strength can be nearly anything. Note that the “minors” versus “two lowest” issue becomes more interesting when the opponents open a “could be short” minor, but I still think it’s best to play as if they have the suit they opened because on average they do.

In certain competitive auctions 2NT can show the minors, even if one of the opponents has bid one of them. This happens when a 2NT can’t possibly be natural (usually because it’s by a passed hand) and when double would be for takeout; 2NT is also for takeout but with an emphasis on the minors. This is very auction-dependent; I’m mentioning it just so you’re aware of the possibility.

DEFENSE VERSUS NOTRUMP

Even on an advanced card I favor playing the same method against an opening 1NT in direct and balancing seat, mostly for simplicity’s sake; the advantages of a different method in balancing seat are small. However, it’s important in tournament play to have a different method for weak notrumps, one that gives you a penalty double, so on this and the advanced card I advocate a split system according to strength.

Technical note that you should feel perfectly fine about ignoring: What’s a strong notrump and what’s a weak one? We could draw the line anywhere but I favor putting it at 16 points, meaning that if the agreed range includes 16 or more high card points as a possibility, it’s strong. Many players put this cutoff at 15 but I think that’s a mistake, at least in North American tournaments, and here’s why:

Players whose range goes to up 15 points are usually playing either 12-15 or 13-15; players whose range goes to 16 are usually playing 14-16. But because average strength hands are the most common and more extreme strengths (weak or strong) less and less common as their strength deviates from 10, the high end of opening notrump ranges is always less common than the low end; this skews the average of every range toward its low end.4 Here are the approximate frequencies for some balanced hands5:

-

- 10 hcp: 9.2% (of 4-4-3-2 hands; very similar for other balanced shapes)

- 11 hcp: 8.8%

- 12 hcp: 7.9%

- 13 hcp: 6.8%

- 14 hcp: 5.4%

- 15 hcp: 4.4%

- 16 hcp: 3.6%

- 17 hcp: 2.4%

You don’t have to crunch the numbers to see that, say, a 12 point hand is a lot more common than a 15 point hand. (The ratio is almost 1.8 to 1.) Using these numbers we can compute the average (mean) high card points for some commonly played ranges for the 1NT opening:

-

- 10-12: 10.9

- 11-14: 12.3

- 12-14: 12.9

- 12-15: 13.3

- 13-15: 13.9

- 14-16: 14.8

- 15-17: 15.8

Glancing at these numbers (goodness knows I don’t expect you to study them hard!), you can see that on average, a 12-15 notrump is a lot weaker than a 14-16. Because those are the common ranges that look similar but have the largest spread, I put the cutoff there, at a 16 count.

Another interesting thing to put under your thinking cap: the average hands are more common effect gets even more pronounced as you consider higher point counts, meaning that at the upper end of the scale the stronger hands are much less frequent. The practical effect is that it’s usually safe to assume partner is on the lower end of his bids, especially if he’s already shown a strong hand. An extreme example: Suppose partner has shown a 22-24 hcp notrump (by opening 2♣ and then rebidding 2NT). He’s about 55% likely to have 22 points, versus 30% for 23 points and just 15% for 24.

End technical note…

Versus Strong (includes 16 HCP) Notrump: meckwell

Playing DONT, which I did list on the basic 2/1 page, is fine but I prefer meckwell, which is similar; the simplicity and ubiquity of DONT is the reason I listed it on the simple card. The main advantage of meckwell over DONT is that with a heart suit you bid 2♥ directly; this takes away responder’s opportunity to show values by redoubling, meaning that against most pairs you’re much more likely to to be permitted to play 2 hearts undoubled. Anyway, here’s meckwell:

- Double can be any of several hands — it shows either a one suiter in either minor or a two suiter with both majors, or (very rarely) some game forcing hand; advancer bids 2♣ and intervenor then passes, bids 2♦ with diamonds, or bids 2♥ to show both majors. With the rare game force, intervenor’s subsequent bidding is natural.

- 2♣ shows clubs and a major (though playing it as clubs and another is fine too); advancer either passes, bids 2♦ to ask for the major, or bids his own major (i.e., 2♥ is natural, not pass or correct).

- 2♦ shows diamonds and a major;

- 2♥ shows hearts;

- 2â™ shows spades.

- 2NT shows both minors and enough shape to belong at that level, or a strong (game invitational or better opposite a random six count, let’s say) hand that doesn’t know where to play but doesn’t want partner to pass at the two level or pass a double.

Versus Weak (less than 16 HCP) Notrump: Modified cappelletti (this is optional; regular cappelletti is fine too)

Double is penalty (which is important to have available against weak notrumps); 2♣ shows either diamonds only, or some major-minor two suiter; 2♦ shows both majors; 2♥ and 2â™ are each natural; 2NT shows minors. As against strong notrumps, higher-level interference is natural and requires a lot of shape. Notice the modification from cappelletti (also known as hamilton), switching the major suit bids so that we show hearts and spades immediately. Bidding 2♥ and 2â™ naturally tends to work pretty well, particularly against inexperienced opponents (who won’t double much) and those playing what are called “stolen bid” doubles (because they can’t double you for penalty, which is why you shouldn’t play them).

After we double, if advancer decides to pull to a suit (which he usually should not do without either great playing strength or a truly terrible hand), his bids are natural. (Many people play their normal 1 notrump systems here — i.e., as if the doubler had opened 1NT — and that’s acceptable too.)

A subtlety: In strong competition a clever idea is to treat all third seat 1NT openings as strong, regardless the announced point count, for purposes of what direct seat action means; this gives you back your penalty double, which you’ll need when opener is fudging or psyching — each of which is common in third seat. Be sure to discuss it with partner before trying this, obviously.

AFTER OPPONENT’S TAKEOUT DOUBLE

New suit forcing at the 1 level only. It’s normal and probably best to play that responder can escape to a new suit at the two level with a long suit and a weak hand, so we play such bids nonforcing.

2NT Response: limit+ after majors and minors. In other words, with a good hand and support for partner, we bid 2NT (artificial, alerted) rather than raise directly; this frees up jump raises to be weak, which is nice to have in competition. This treatment is often called either jordan or dormer. One implication of playing this way is that redoubling instead of raising or bidding 2NT suggests, but does not promise, that responder has no great fit for opener’s suit; note that the redouble shows about 10 or more points and asks opener to double (for penalties) anything the bad guys bid if possible, and usually to pass otherwise.

This treatment is optional, but nice to have. One way to remember it is that 2NT should almost never be natural in a competitive auction. Playing 2NT is rarely a great deal in competition, especially if the opponents have a fit, as usually it’s better either to play in a suit or to double the bad guys. (Of course, determining which one is best can be tricky…)

Versus Opening Preempts Double is Takeout through 4♥ (penalty above that). Note that “takeout” doubles are left in (passed for penalties) more and more often as the level gets higher.

SLAM CONVENTIONS

Gerber. Gerber is a bid of 4♣ that is used conventionally to ask for aces (not keycards — there’s no trump suit). While for some players, particularly those who’ve been playing since the 50s or earlier, a 4♣ bid is usually or always gerber, I don’t recommend that approach; instead, play that 4♣ is gerber only in certain very particular auctions that always involve partner having bid notrump:

- If partner’s last bid was in notrump and notrump is a possible strain (i.e., the notrump bid was natural and we have not found a 4-4 or better major suit fit), and neither player has bid clubs naturally or otherwise shown that suit, then 4♣ is gerber.

- If partner’s first bid was a natural (not unusual) notrump bid (including an overcall) and no suit fit has been found, then a jump to 4♣ is gerber unless there is a specific agreement that it is something else. (The specific agreement we’re worried about is usually a splinter bid.)

When 4♣ is not gerber it can be natural (usually part of a slam try), a splinter bid, a control bid, or certain other conventions once we start adding things on the advanced card.

Neither Gerber nor any other ace-asking bid is alerted during the auction unless it occurs on the first round of the auction; starting with opener’s second bid, no bid of 3NT or more is alerted until after the auction is over.

1430 Keycard. The choice between 1430 (wherein a 5♣ answer to a 4NT keycard inquiry shows one or four keycards, a 5♦ bid 0 or 3) and 3014 (wherein these two answers are reversed so a club bid shows the lower total; this may seem more natural and is the original version) is incredibly close; it matters only in specific auctions in which hearts are trump, plus a very rare auction in which clubs are trump and 4NT is the keycard ask. Most of the time the choice is irrelevant. I listed 1430 here because it’s slightly better unless you’re doing some other stuff (which we add on more complicated cards) and it’s more popular among serious players, but really it’s fine to do whatever your partner prefers.

Whichever you choose, the third step (5♥) shows two [or five!] keycards without the queen of the agreed trump suit, and 5♠shows 2 or 5 with the queen).

Queen ask. The queen ask is part of keycard (1430 or 3014) but let’s make it explicit: After a keycard ask and an answer that neither shows nor denies the queen of trump (i.e., 5♣ and 5♦ don’t say anything about the queen; 5♥ and 5â™ do), the cheapest bid that is not a possible contract (in other words, it’s neither the agreed trump suit nor anything else that the bidder might want to sign off in if the trump suit has already been passed) asks for the queen of the agreed trump suit. In answering a queen ask, return to the trump suit at the cheapest level (which should be five unless something has gone wrong) without the queen, and do something else with it: either bid a side-suit king (the cheapest you can show) if you have one or bid six of the agreed suit if you have no side king.

A rare auction that sounds similar but means something entirely different: Suppose a minor suit is agreed, someone asks for keycards with a 4NT bid, and the response is higher than five of the agreed suit. A 5â™ bid now, by the player who asked using 4NT, is a marionette to 5NT (i.e., it’s a near demand that partner bid 5NT). The usual reason for using this bid is a desire to sign off in exactly 5NT, because the player who asked has learned that the partnership is missing two keycards but the bidding has gone beyond the safe five a minor contract.

A subtle addition: If you can tell from the bidding that the partnership definitely has at least ten cards in the agreed trump suit, then bid as if you have the queen even if you don’t. With a ten card fit you will lose a trick to the queen only if you’re very unlucky (about 5% of the time), so it’s reasonable to ignore that possibility in judging whether to bid slam.

Another addition that you don’t need to worry about unless you’re comfortable with it: If partner asks you for keycards, you answer, and partner then signs off in five of the agreed suit, then you can raise to 6 if three things are all true:

- You have the higher number of keycards that is consistent with the answer you gave (for example, you answered 5♣ showing 1 or 4 and you have 4);

- It’s possible that partner does not already know you have the higher number (consider as a counterexample: you opened 2♣ and later showed 3 or 0 — partner will assume, correctly, that a 2♣ opener can’t have zero keycards); and

- Partner didn’t bid five of the trump suit noticeably slowly.

The last point, that partner can’t have signed off slowly, isn’t part of the system but it’s a concession to practicality: When partner spends a long time thinking and then signs off short of slam, you have unauthorized information that he was thinking about going further. In practice the directors probably won’t give you the benefit if you bid on and it’s right to do so (i.e., they’ll adjust the score to 5 making 6, if slam does make) even if you otherwise would have. You can argue that bidding on is obvious but that argument probably won’t be successful.

If you have all five keycards and for some reason partner is the one doing the asking, you should never pass an attempted signoff at the five level. What more could partner be looking for?

Specific king ask. After a 4NT keycard inquiry and any response, a bid of 5NT asks for kings (not counting the king of the trump suit, which we already counted as a keycard). The same applies if a second round inquiry was necessary to ask about the trump queen. Respond by bidding the cheapest king you can show below 6 of the trump suit. Notice that if hearts are trump you won’t be able to show the spade king, which is a weakness that we handle on more complex versions of the card; if a minor suit is trump this method works pretty badly, which is why we try not to use 4NT keycard in minor suit auctions at all. There are better ways, but for now this will do.

If you don’t have any side kings you can safely show, bid six of the agreed suit. Also, if you don’t have any showable kings but you know for sure that you have a source of tricks that should be enough for partner (who must be looking for a grand slam, else why ask for kings?), then you can bid the grand yourself. This is rare but it does happen when you have a solid source of several tricks, one you haven’t told partner about, in a suit that’s higher than the agreed trump suit.

If you are comfortable showing the number of side kings in response to 5NT, rather than specific kings, that’s fine too; specific kings is only a little bit better.

OPENING LEADS

Versus Suits: Standard honor leads (i.e., top of a sequence, including an internal sequence). Ace from Ace-king (which is standard these days even if the card implies otherwise); playing the king first would imply a doubleton.

Fourth best from length (when you don’t have a sequence to lead). Low from three, whether you have an honor or not. (“Top of nothing” is playable but I prefer this method; leading the middle card is a poor method.) Top of a doubleton (except ace-king).

Versus Notrump: About the same as versus suits, with a few exceptions:

Honor sequence leads against notrump require three cards (possibly with a single card missing, as in KQT versus just KQx), and lead the king, not the ace, from AK combinations (which should be AKJ or better except from exactly AKx). As for spot cards, lead top of nothing if you’ve chosen to lead from three small cards; rarely lead a doubleton against notrump unless partner bid the suit but if you do, lead high. It’s also OK to lead the second-highest card (or the highest, if you’re sure it won’t be needed to take a trick) when you’ve chosen to lead from exactly four cards without any honors (though usually you should lead a different suit).

DEFENSIVE CARDING

Upside-Down Count and Attitude (against suits and notrump). It is fine to play “standard” (high encourages, high for even count), but somewhat better to play “upside-down” (low encourages, low for even count). It’s also not hard to make the switch because you get tons of hands on which to practice — after all, you defend about half the hands you play and you should be signalling on most of those.

Using upside down attitude and standard count is playable but generally considered a poor combination, and in my experience is considerably harder to do well. Many players do play this way but I urge you to switch to upside down count and attitude (UDCA) instead.

Reverse smith echo. An optional addition, but a very nice one to have available. Playing smith, which applies only against notrump contracts, both defenders signal their attitude about continuing the suit of the opening lead, as follows: Suppose declarer has won either the opening lead (usually) or defenders’ continuation in the same suit, and suppose that based on the bidding, the cards already played, and dummy’s holding it is not obvious whether one, the other, or both defenders should continue attacking the same suit when they regain the lead. If this is the case, each defender signals attitude about her partner continuing the suit, using spot cards in the suit declarer next attacks. In reverse smith, which I find easier to learn and remember, an unnecessarily high spot card from either player asks partner not to continue the suit that was originally led. This discouraging signal can be made because doing so would be unsafe from one side or the other (perhaps the suit needs to be continued only from the correct side), or there’s a more fruitful line of defense; the latter will often be the case if the opening lead was from a short (two or three card) holding, hoping to hit partner’s suit.

If you play smith, it’s important to know when it doesn’t apply. The obvious exception is when the correct defense is, well, obvious (picture dummy with a triple stopper remaining, for example); in such cases defenders’ cards retain their normal meaning, whether count or suit preference. But there’s an important specific exception too: When dummy has a source of tricks (a long, strong suit) but is missing a high honor or two, and has no outside entry (or is missing two top honors and has only one entry), and declarer starts to drive out defenders’ stopper(s) in that suit, it is very important for the defenders to show count in the suit declarer is attacking (so they know how long to hold up) so that’s what their spot cards should show.

Of course it may be impossible to read whether partner has used a Smith echo until she plays a second spot card (which will reveal whether the order was high-low — an echo — or low high — no echo), but if you have to decide before you can be sure, do your best. This applies to any high-low signal.

A reminder: A smith signal is never a command — no signal is. If you know what to do, do it.

Primary signal to partner’s leads: Attitude. Attitude is your first priority in all carding, whether following to partner’s lead or discarding. When attitude has been shown already or is obvious (for example, it’s declarer’s suit), the next priority is count. In certain specific circumstances suit preference is the signal but it’s fine not to worry about that for now; as you gain experience you’ll probably show suit preference more and more often.

Notes

- Bridge Winners is a discussion board that you might consider joining (it’s free and they don’t spam you); some of the discussions get silly — it’s the internet, after all — but there’s also a lot of good information available there.

- Regarding suit lengths: I follow the method used by The Bridge World magazine (and others), wherein one uses hyphens to denote generic hand shapes and equal signs to show specific shapes. Thus, for example, 5-3-3-2 denotes any hand with a five card suit, two three card suits, and a doubleton, while 5=3=3=2 shows specifically five spades, three hearts, three diamonds, and three clubs.

- Regarding pronouns: There is no universally accepted treatment of personal pronouns in English when the person’s sex is unknown. What I’ve settled on for all my bridge writing is this: Opener and fourth seat is “he”, responder (opener’s partner) is “she”, intervenor (the player who first doubles or overcalls) is “she”, and advancer (the partner of the intervenor) is “he”. This works out to be darned close to 50/50 over the course of a typical writeup.

- If the ranges were less than average strength this effect would be reversed, but an agreement to open 1 notrump with less than average strength isn’t allowed in ACBL play.

- I got these number’s from Richard Pavlicek’s excellent site; the tables I used are on this page. Here I’m considering only 4-4-3-2 hands as a proxy for all balanced hands